Copy Protection of Dungeon Master for Apple IIGS

Overview

This document provides a detailed description of the copy protection sector found on the Dungeon Master for Apple IIGS floppy disks.

You may get an overview of the copy protection, including on other platforms, on Copy Protection.

All versions of Dungeon Master for Apple IIGS were studied:

- Dungeon Master version 2.0 English

- Dungeon Master version 2.1 English

Note that Dungeon Master Demo version 1.4 is not copy protected.

This page is based on the study of some .a2r disk images created with Applesauce that are available online:

- Two disk images of two distinct copies of Dungeon Master version 2.0 English for Apple IIGS supplied by danc256 here

- Dungeon Master - Disk 1.a2r *

- Dungeon Master - Disk 1 - copy 2.a2r *

- Two alternate disk images of the same two floppy disks also supplied by danc256 here

- Dungeon Master - Disk 1.a2r

- Dungeon Master - Disk 1 - copy 2.a2r

- Two disk images of the same copy of Dungeon Master version 2.1 English for Apple IIGS supplied by Antoine Vignau here

- Dungeon Master - Disk 1.a2r (5 revolutions)

- Dungeon Master - Disk 1 - copy 2.a2r (7 revolutions) *

Because of the duplicate images, only the 3 disk images marked with an * were used for this document.

Technical background

Please read Basics of data storage on floppy disks if you are not already familiar with the way data is stored on floppy disks because this is required to understand how the copy protection works.

Encoding data

Floppy disks on Apple IIGS do not use the MFM encoding that most computers of that time were using. Instead it uses an encoding named ‘Group Coded Recording 6 and 2’ (GCR). This encoding ensures that there are never more than two ‘0’ bits in a row stored on the floppy disk. The encoding and decoding processes are called nibblizing and denibblizing, and they both rely on a translation table between 6 bits of user data and 8 bits of disk data. Both are explained in detail in chapters 1.3.1.3 and 1.3.1.4 of the uPD72070 Floppy Disk Controller datasheet (note that this is not the FDC used in the Apple IIGS, but it is compatible with the GCR encoding).

A reference 6-and-2 encoding table is also available here

Synchronizing the FDC

The FDC needs a clock so that it knows the rate at which it should output data bits interpreted from the electrical signal it receives from the floppy disk drive. For this purpose, it uses an ‘inspection window’ which is a time frame during which the FDC waits for an electrical pulse (a flux reversal) to occur.

In the ideal situation, each bit of data represents a 2µs time frame. Because of the ’no more than two consecutive 0 bits’ rule, only three patterns can occur after a ‘1’ bit (a flux reversal): ‘1’, ‘01’ and ‘001’, which respectively represent 2µs, 4µs and 6µs time frames. The FDC resets its inspection window after each flux reversal and then waits for the next one. When the next flux reversal occurs, the FDC outputs the data bits corresponding to the time elapsed since the previous reversal (with some tolerance to account for speed variations between different disk drives and also between each rotation on the same drive).

Reading bytes

When the FDC starts reading bits from the disk, it will start at the random location on the track that the head is above, which may be right in the middle of a byte. Here is how byte boundaries are found in the large stream of bits that is read from the disk:

- The FDC reads bits from the disk and shifts them into an eight bit register from the right. It considers that a byte was read only when the most significant bit is ‘1’ and then outputs this byte of data.

- A special sequence of bytes called ‘self-synchronization bytes’ is written to the disk: $FF $3F $CF $F3 $FC $FF. It is also represented as FF(10) FF(10) FF(10) FF(10) FF where FF(10) means a ten bits byte, which consists of eight ‘1’ bits followed by two ‘0’ bits.

These four special ten bit bytes force the FDC to align itself on byte boundaries because of the rule above: if 8 bits are read from the disk but a ‘0’ bit is in the most significant bit of the read register, then reading continues and that ‘0’ bit is ignored, which causes the FDC to skip a bit in the stream. After four such special self-synchronization bytes, the FDC is guaranteed to be synchronized. For more information about self-synchronization bytes, you can read pages 3-8 to 3-11 of ‘Beneath Apple ProDOS’

All sector fields start with self-synchronization bytes to make sure the address and data prologues (and the following data) are read correctly. When a sector is written to the disk, the sector address field is not overwritten, but the whole sector data field is overwritten, including the preceding self-synchronization bytes.

Track layout

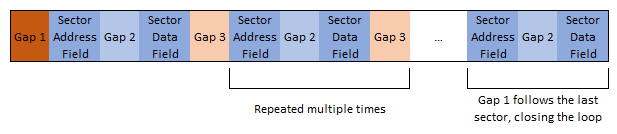

When a floppy disk is formatted, each track is written at once. The design ensures that the last bytes written on a track will wrap around and overwrite some the first bytes that were written on the same track, so that no part of the track is left unformatted. For that reason, the first bytes written are not user data bytes: they form what is called a gap and gaps only contain self-synchronization bytes.

Each track is structured as a series of sectors separated by gaps. The first gap (Gap 1) is longer than the others (Gap 3) for the reason above. Each sector has two parts, an address field and a data field which are also separated by a gap (Gap 2).

Gaps provide some tolerance for the start and end locations of individual sectors: when an individual sector is written to the disk after it was formatted, the start and end locations of the written sector cannot be perfectly aligned with the previous sector content because of imprecision and small rotation speed differences. Gaps are also useful to give enough time to the FDC and CPU to process a sector address field before reading the following sector data field starts.

Gap 1 consists of up to 128 self-synchronization bytes (between first and last sector stored on the track). The purpose of this long gap is to make sure that the end of the last sector data field on the track will overwrite the beginning of this gap, ensuring the track is fully used and taking into account speed variations from drive to drive.

A regular sector has the following structure (these details are useful for comparison with the copy protection sector). This example is sector 5 on track 0 side 1 which is physically located right before the copy protected sector:

On this screenshot, the sector data is highlighted on the scatter graph on the top and shows only regular timing values of 2µs, 4µs and 6µs.- Gap 3 (between sectors): $FF $FF followed by seven self-synchronization patterns $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF

- Sector address field: Identifies the sector. This information is searched for when reading a sector.

- Sector address field prologue: $D5 $AA $96. All sector address fields start with this byte sequence.

- Sector information: $96 $9E $D6 $D9 $A6. Using the GCR 6 and 2 table, these bytes decode to the 6 bit values $00 $05 $20 $22 $07 which have the following meaning:

$00 00ttttttLow order 6 bits of track number = 0$05 00ssssssSector number = 5 (= logical block 17 because it is on side 1 and track 0 on side 0 contains 12 sectors, 12 + 5 = 17)$20 00ntttttn is side 1 (0=side 0, 1=side 1). ttttt are the high-order 5 bits of track number = 0$22 00h0iiiih is number of sides = double-sided (0=single, 1=double). iiii is the interleave = 2$07 00ccccccChecksum of 4 previous bytes using exclusive OR: ((($00 XOR $05) XOR $20) XOR $22) = $07 - Sector address field epilogue: $DE $AA. All sector address and data fields end with this byte sequence.

- Gap 2 (between sector address field and sector data field): Self-synchronization pattern $FF $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF. This gap is usually five to ten bytes long. It may get larger when the sector data is overwritten: there is some tolerance regarding the start location of the write operation so it may occur anywhere within these initial synchronization bytes, and it will probably break one of those bytes. If writing starts in the last synchronization byte, the write operation will add its own five bytes of synchronization and thus increase the length of the gap. When this occurs, the first bytes of the gap located after the sector data are also overwritten, which is exactly the purpose of having gaps: to allow some tolerance for the start and end locations of written sector.

- Sector data field (709 bytes): The actual sector contents structured as:

- Sector data field prologue (3 bytes): $D5 $AA $AD. All sector data fields start with this byte sequence.

- Sector number (1 byte): this is a copy of the byte containing the sector number in the sector address field.

- Data bytes (699 bytes): Encoded with GCR 6 and 2 = 524 bytes after decoding = 12 tag bytes (used on Macintosh but not used on Apple IIGS where they always have $00 values, hence the sixteen $96 bytes visible at the beginning of each sector) + 512 user data bytes.

The following screenshot shows the decoded data of sector 5. Note that sector 11 (the copy protection sector) cannot be decoded because of its non-standard content. - Checksum (4 bytes): Encoded with GCR 6 and 2 = 3 bytes after decoding. Used to check that sector data is not corrupted.

- Sector data field epilogue (2 bytes): $DE $AA. All sector address and data fields end with this byte sequence.

- Gap 3 (between sectors): $FF $FF followed by 7 self-synchronization patterns $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF

Note: Sector prologues use $D5 and $AA bytes to mark their beginning. These are reserved codes that are not part of the GCR 6 and 2 encoding table.

Floppy disk formats

There are many possible floppy disk formats that use varying numbers of tracks, sectors per track and sector sizes. The format of a floppy disk is defined when the disk is formatted. When a floppy disk is formatted, each track is written at once (not sector by sector), thus defining the number of sectors and their size, the size of gaps, etc. This operation is called low-level formatting. High-level formatting means installing a file system on the floppy disk. Usually low and high level formatting are performed together.

The standard Apple IIGS floppy disk format is the Apple double-density, double-sided 3.5" floppy disk format that was also used on Macintosh computers. The file system is different though: ProDOS on Apple IIGS, MFS or HFS on Macintosh.

The format has 80 tracks per side (numbered 0 to 79), 8 to 12 sectors per track (5 zones of 16 tracks each) and 512 bytes of data per sector.

In order to maximize capacity, there are more sectors on the outer tracks than on the inner tracks, and the drive has a different rotation speed in each zone:

The storage capacity is: 2 sides x 16 tracks x (8 + 9 + 10 + 11 + 12) sectors per track x 512 bytes per sector = 819200 Bytes = 800 KB.

Sectors are not physically stored in their logical order, they are ‘interleaved’. For example on track 0, sectors 0 to 11 are physically stored in the following order on the circular track: 0 6 1 7 2 8 3 9 4 10 5 11.

Copy protection sector

Overview

All versions of Dungeon Master for Apple IIGS use the standard floppy disk format.

Track 0 on side 0 contains a standard Apple IIGS boot sector and file system.

There is one special sector for the copy protection: logical block $17 = 23, physical sector 11 on track 0, side 1. This is the last on the track, meaning that Gap1 (the largest) follows it and then there is sector 0. This sector is part of the file named BAD.BLOCKS in the file system.

The remaining sectors in track 0 and all sectors in other tracks are used to store the game’s files. These other sectors will not be described further in this document as they are completely standard and just contain the game’s program and data files.

The copy protection sector contains fuzzy bits: bits of raw data that have a random value (0 or 1) when read multiple times.

This sector cannot be read as a normal sector: The game contains a special routine to read the raw GCR encoded data from the disk and never tries to decode this data. The copy protection checks are performed directly on the raw data.

This sector cannot be copied with the Apple IIGS hardware because:

- A sector copier would find the sector 11 address field but it would fail to read the following sector data field because the sector number there is not 11 (the sector numbers must match in both fields). Even if the sector number was correct, the sector contains $A9 and $AA values that are invalid in the GCR 6 and 2 encoding (this is why they are highlighted in Applesauce screenshots), and also the sector checksum would be incorrect.

- A bit copier would fail to copy the sector accurately because of the special timings that cannot be reproduced. The FDC can only write with standard timings, and the randomness caused by special timings would be lost.

Sector contents

On this screenshot, the sector data is highlighted on the scatter graph on the top and shows lots of abnormal timing values between the regular values of 2µs, 4µs and 6µs.- Gap 3 (between sectors): $FF $FF followed by seven self-synchronization patterns $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF(10) $FF

- Sector address field: Identifies the sector. This information is searched for when reading a sector.

- Sector address field prologue: $D5 $AA $96. All sector address fields start with this byte sequence.

- Sector information: $96 $AD $D6 $D9 $AB. Using the GCR 6 and 2 table, these bytes decode to the 6 bit values $00 $0B $20 $22 $09 which have the following meaning:

$00 00ttttttLow order 6 bits of track number = 0$0B 00ssssssSector number = 11 (= logical block 23 because it is on side 1 and track 0 on side 0 contains 12 sectors, 12 + 11 = 23)$20 00ntttttn is side 1 (0=side 0, 1=side 1). ttttt are the high-order 5 bits of track number = 0$22 00h0iiiih is number of sides = double-sided (0=single, 1=double). iiii is the interleave = 2$09 00ccccccChecksum of 4 previous bytes using exclusive OR: ((($00 XOR $0B) XOR $20) XOR $22) = $09 - Sector address field epilogue: $DE $AA. All sector address and data fields end with this byte sequence.

- Gap 2. See ‘Gap Comparison’ section below.

- Sector data field (709 bytes): The actual sector contents. The sector size is the normal size, however the structure of its content is different.

Sector data field prologue (3 bytes): $D5 $AA $AD. These values are checked by the copy protection code to identify the beginning of the sector data.

6 bytes: Date and serial number. These bytes are never checked by the game. They have different values on each copy of the game so this is similar to the serial number used in the Atari ST / Amiga copy protected sector (see Detailed analysis of Atari ST Floppy Disks of Dungeon Master and Chaos Strikes Back).

- Byte 0: Year: Encoded as year number - 1988. 0 means 1988, 1 means 1989 etc.

- Byte 1: Month: 1 to 12

- Byte 2: Day: 1 to 31

- Byte 3: Serial number: most significant 4 bits of the 16 bit serial number

- Byte 4: Serial number: middle 6 bits of the 16 bit serial number

- Byte 5: Serial number: least significant 6 bits of the 16 bit serial number

Here are the values of these bytes in the copies that were studied:

- $97 $97 $BE $96 $CB $AC decodes to $01 $01 $19 $00 $1B $0A in “Dungeon Master - Disk 1 - sdancer_a2rs.a2r” (Dungeon Master version 2.0). Date: January 25, 1989. Serial number 0x06CA = 1738

- $97 $97 $D3 $96 $F2 $A7 decodes to $01 $01 $1F $00 $33 $08 in “Dungeon Master - Disk 1 - copy 2 - sdancer_a2rs.a2r” (Dungeon Master version 2.0). Date: January 31, 1989. Serial number 0x0CC8 = 3272

- $97 $9E $B3 $97 $FE $CD decodes to $01 $05 $0F $01 $3E $1C in “Dungeon Master - Disk1.a2r” posted by Disk Blitz (John Morris) in Apple II Infinitum (Dungeon Master version 2.0). Date: May 15, 1989. Serial number 0x1F9C = 8092

- $96 $AE $BD $9B $BD $BE decodes to $00 $0C $18 $03 $18 $19 in “Dungeon Master - Disk 1 - copy 2 - Antoine Vignau.a2r” (Dungeon Master version 2.1). Date: December 24, 1988. Serial number 0x3619 = 13849. This date is strange because version 2.1 was released towards the end of 1989. Maybe this disk was prepared in 1988 and reused for version 2.1 later, or the date configured on the computer where the serial number was written was incorrect at the time the serial number was written.

If the sector was a regular sector, the first byte should contain the sector number (11 = $0B encoded as $AD using GCR in 6 and 2). As its value does not match the sector number in the preceding sector address field, any read attempt using the sector number will fail.

4 bytes $FF $FF $FF $FF. Checked by the copy protection code.

690 bytes: 345 pairs of $B2 $EF bytes, divided in 11 series of 32 bytes, except the first that is only 31 bytes and the last that is only 26 bytes (The same series are found in all of the three copies that were studied): in each series, each $B2 byte contains one flux reversal that is slightly shifted compared to the preceding $B2 byte. The timing of this reversal goes from one normal timing to another normal timing but some of the intermediary values are guaranteed to be ambiguous and cause the fuzzy bits effect. The resulting value read by the FDC is either $B2, $A9(9) or $AA. The values of all these bytes are checked by the copy protection code (alternating values of $EF and one of the three possible values of $B2, $A9, and $AA).

The animation below (from Dungeon Master - Disk 1 - sdancer_a2rs.a2r) shows the flux reversal shifting from left to right (32 images from the second series, captured from Applesauce software). Other reversals also move slightly on the animation but only within the margin of tolerance so the corresponding decoded data does not change.

The reversal in the center of the animation slowly moves from left to right, and the byte value above shows how the FDC would decode it:

Because of small fluctuations in the disk rotation speed, and the spreading of the flux reversal timings, there are always some ambiguous flux reversals that cause two readings to contain different bit values, causing the fuzzy bits effect that is checked by the copy protection code.

Each byte containing a fuzzy bit produces one of three possible values after being read by the FDC. Note that the first three bits and the last three bits are always the same:4 bytes $FF $FF $FF $FF. Checked by the copy protection code.

Sector data field epilogue (2 bytes): $DE $AA. These values are checked by the copy protection code to identify the end of the sector data.

- Gap 1: Because the copy protected sector is the last one on the track, it is followed by a Gap 1 and not a Gap 3. See ‘Gap Comparison’ section below.

Gap comparison

The following screenshot compares the Gap 2 content of the copy protection sector 11 (between the sector address field and the sector data field):

The length of the gap 2 is not the same in all copies, and always longer than the length in regular sectors:

Similar differences are visible at the end of the sectors where the write stopped right after the $DE $AA epilogue. The first few bytes afterwards are not decoded as $FF because the write stopped in the middle of what was previously written on the disk. After at most four $FF(10) synchronization bytes, the decoding is fine again (and this is exactly the purpose of the synchronization bytes).

All other gaps in the studied disk images are very ‘clean’ (and identical for all sectors of all copies) except the two gaps before and after the copy protection sector data field, which are also a little different on each copy. This suggests that the disks were produced in two steps:

- Each track was written at once, directly containing all the final data and using a fully normal format.

- Sector 11 on track 0 side 1 was later overwritten with the special copy protection sector contents. The write operation did not start exactly at the same location in the Gap 2 preceding the copy protection sector in all copies, and it also did not end at the same location in the Gap 1 following the copy protection sector. This explains why the decoded data in these gaps is not identical to the gaps in other sectors and tracks.

History of this document

- Version 1.0, December 29, 2020

- First release.